In May, the world watched as Epic Games dragged Apple to court, challenging the most profitable company in the world in the name of app fairness (and securing more Fortnite profits for itself). We’re still waiting for a verdict in Epic v. Apple, but we haven’t just been sitting around. We’ve also been digging through these companies’ dirty laundry, reading scores of internal emails and confidential presentations unearthed during the legal discovery process. It’s fascinating stuff.

In fact, we found dirt on a variety of other companies as well: Microsoft, Sony, Google, Nintendo, Valve, Netflix, Hulu, and many others were caught up in discovery, and many details of their businesses, strategies, and conversations with Apple and Epic are now out in the open, publicly released by the courts.

After sifting through over 800 documents spanning 4.5 gigabytes, here are the roughly 100 things I learned.

Netflix had a “unique arrangement” with Apple to share only 15 percent of its revenue on iOS, half of Apple’s standard rate, and it was arguing to pay even less.

Last July, Apple CEO Tim Cook testified under oath before Congress that “we treat every developer the same.” But as previously unearthed documents revealed, Apple was more than willing to give Netflix all sorts of special treatment to keep its cut of Netflix’s subscription fees.

Here’s something I haven’t seen previously reported, though: it appears Apple had already given Netflix a sweetheart deal where it took just 15 percent of subscriptions Netflix sold in its app. Normally, subscription services on iOS pay 30 percent the first year, and it goes down to 15 percent if users stay subscribed for year two, but this passage suggests Apple offered Netflix something different:

Apple wanted Netflix to renew this special arrangement in 2018 instead of dropping in-app purchases all together, and it thought Netflix might agree — because if it didn’t, its “current subs in year 1 would pop up from 15% to 30%,” wrote Apple subscription services manager Peter Stern, something App Store chief Phil Schiller confirmed.

The email chain reveals Netflix had this arrangement before Apple created an “Apple Video Partner Program,” which offers the same reduced cut in exchange for supporting Apple features like in-app purchase, AirPlay, Universal Search, and the Apple TV app, several of which Netflix rejected in 2019. Apple’s Partner Program page says “over 130 premium subscription video entertainment providers” are signed up, including Amazon Prime Video, Disney Plus, HBO Max, and Starz. No mention of Hulu or Netflix.

Apple isn’t the only one that quietly allows some companies to bypass its full cut — Microsoft Xbox does, too.

In a presentation titled “Microsoft Store Revenue Share & Exceptions Overview — January 2021,” Microsoft reveals that 13 of its top 18 app partners have struck alternative deals.

Some pay just 10 percent of subscriptions instead of 15 percent, one pays just 7.5 percent, one pays $1.87 per month per subscriber, another pays $1.50 per registered user, and — it’s partially redacted, but it seems likely from context — it appears Amazon Prime Video gives Microsoft a percentage of a subscriber’s first two months, plus a 5 percent cut of any add-on video services.

Two of Microsoft’s top 13 PC gaming partners pay less than the standard 30 percent, too: King paid just 12 percent, and another unnamed “Casual Games” partner — Microsoft’s #3 PC partner with $49.6M in Microsoft Store revenue — paid 20 percent instead of 30.

Microsoft has now reduced its cut to 12 percent for games and as little as 0 percent for apps, at least in its Windows app store. But Microsoft is still asking for its 30 percent of games on Xbox.

Microsoft may have scrapped a plan to reduce its cut of Xbox games to 12 percent, too.

In the same document, we spotted that Microsoft originally planned to move to a smaller cut for both Xbox and Windows games this year. “All games will move to 88/12 in CY21” appears twice in the presentation, under both “Microsoft Store on Windows 10” and “Microsoft Store on Xbox.”

However, Microsoft told The Verge in May that “we will not be updating the revenue split for console publishers.”

Apple executives once considered lowering its App Store fee.

In July 2011, Phil Schiller suggested the 70/30 split won’t last forever, suggesting Apple could tweak it to stay competitive: “Once we are making over $1B a year in profit from the App Store, is that enough to then think about a model where we ratchet down from 70/30 to 75/25 or even 80/20 if we can maintain a $1B a year run rate?”

For context, Apple made an estimated $64 billion from the App Store in 2020.

Early on, Apple wondered aloud whether it should ever allow sideloading — and whether Apple should publish App Store Guidelines publicly.

Here’s what Schiller told Steve Jobs in November 2009, one year after the App Store debuted:

Steve Jobs personally approved the text users would see when they sideload an app, all the way back in May 2008.

Just two months after declaring that “the App Store is going to be the exclusive way to distribute iPhone applications,” iOS chief Scott Forstall asked which of these two templates Jobs preferred: “The application ‘Monkey Ball’ from the developer ‘Sega’ did not come from the App Store. Do you want to open it?” or “Are you sure you want to open the application ‘Monkey Ball’ from the developer ‘Sega’?”

Jobs picked the latter.

iphone 5 fortnite case

Remember the iPhone SDK’s original restrictive nondisclosure agreement that threw some developers for a loop? Steve Jobs asked Phil Schiller to justify that NDA just two months before the company axed it.

Jobs’ chief concern: whether universities might decide to teach students to develop apps for Android instead of the iPhone. The company got rid of the NDA shortly after this.

There really was an “iPhone nano” in the works, a Steve Jobs email confirms.

When preparing the agenda for a 2011 corporate strategy presentation, Steve Jobs discussed plans for a “Jony,” presumably legendary Apple design director Jony Ive, to show off a model and renderings of an iPhone nano. As Obi-Wan Kenobi famously said, that’s a name I’ve not heard in a long time, not since a series of rumors that Apple was working on a phone that would have been even smaller than the iPhone 4 — the 3.5-inch device we now regard as the pinnacle of one-handed Apple designs.

Here it is: proof that those rumors had basis in reality.

Phil Schiller initially saw Amazon’s Appstore as a huge threat.

“I have one correction to make, the ‘threat level’ is not ‘medium’, it is ‘very high,’” he wrote in March 2011, commenting on an executive summary forwarded to him and other top App Store managers a week after Amazon first launched its Android marketplace.

“Just because there are some obstacles today (install process and security for app downloads) does not mean the threat is much reduced,” he wrote. And while the Amazon Appstore did not wind up being much of a competitor to the App Store or even Google Play, and Amazon’s Fire Phone was an instant flop in 2014, Microsoft will soon use Amazon’s store to bring Android apps to Windows 11.

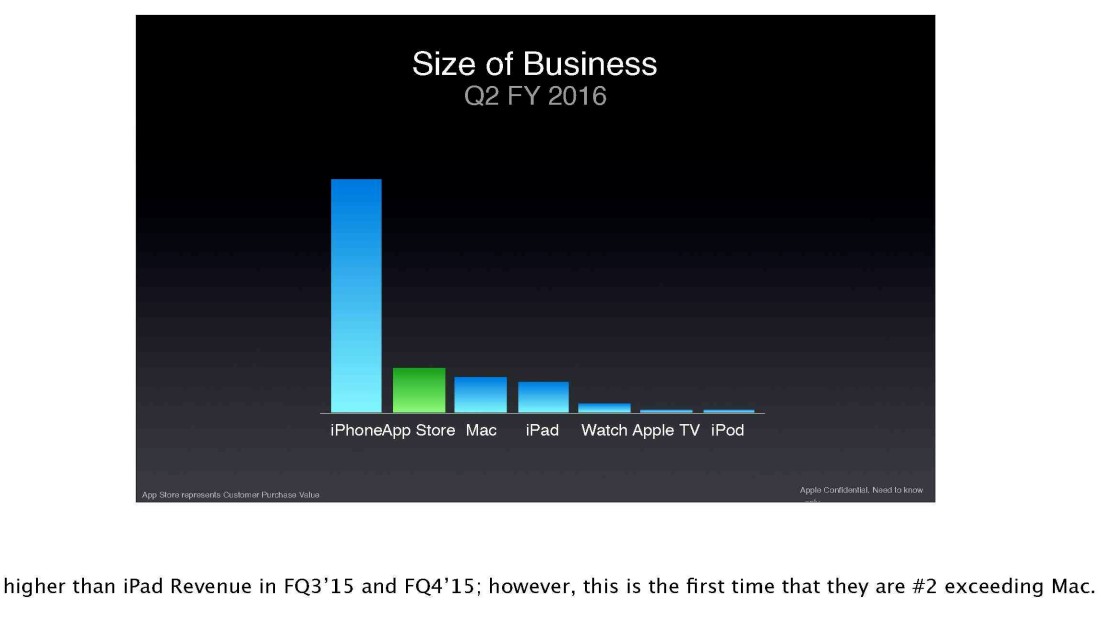

2016 was the year when the App Store business grew bigger than the iPad or Mac business.

We first noticed Apple had become a services company in April 2016, when a down quarter revealed its services business had grown larger than the Mac, but it turns out that’s not quite precise enough: it was the App Store, specifically, that had exploded, according to an internal presentation.

If Apple pursued its original idea, the App Store Small Business Program might have only given developers credit to spend on Apple’s own App Store search ads — not 15 percent back in their pockets.

Phil Schiller called it “Jump Start” in June 2018, and it would have given half of Apple’s 30 percent commission back to first-year developers to spend on ads. “I think it is important for this to be seen as an App Store program for all small developers, not an iAd program to get developers into iAds (though one would hope they love iAds and would see the benefit,” Schiller wrote.

Instead, under the pressure of criticism, antitrust investigations, and legal threats, Apple opted to give half of its 30 percent commission to small developers, period, so long as they stay under $1 million in annual sales.

Apple has long been accused of making self-serving decisions around the App Store, and Epic was quite happy to put some of them on display during the trial. But while these examples below might have been cherry-picked by Epic to serve its purposes, they provide a rare look at how cutthroat Apple executives can be — something that doesn’t always mesh with the public image Apple presents at its keynotes and developer events.

June 2008: Apple sees Google Latitude as a threat.

Days before the launch of Apple’s App Store and months before the first Android smartphone goes on sale, Google appears to be negotiating fruitfully with Apple to bring Google’s Friend Finder (which you may know as Google Latitude) to the iPhone. But Steve Jobs worries that Google contacts may “lead to people not using our contacts app at all.”

Google winds up not releasing Latitude on the iPhone until July 2009, and even then, only as a web app, explaining, “Apple requested we release Latitude as a web application to avoid confusion with Maps on the iPhone, which uses Google to serve maps tiles.”

November 2009: Apple warns PayPal to stay away from its developers.

PayPal, already one of Apple’s official payment partners for iTunes, sees an opportunity with apps. PayPal CEO John Donahoe reaches out to refresh the Apple relationship, saying, “We anticipate that there a growing number of developers adding Paypal into their iPhone applications.” Phil Schiller seems to take this as a threat, replying that the App Store is the only payment mechanism and that developers using PayPal would be violating their agreements with Apple. “I hope that does not become the case,” says Schiller.

October 2010: Steve Jobs declares lock-in will officially be a company strategy now.

In the agenda notes for a 2011 corporate strategy presentation, to be delivered by Jobs himself, he calls 2011 the “Year of the Cloud,” and makes one of its three tenets to “tie all of our products together, so we further lock customers into our ecosystem.”

We have 0 fortnite phone cases, all designed and printed in the uk, ready to buy online today. This case provides a protective yet stylish shield to your iphone se 3rd gen 2022 from accidental drops and scratches. 4.2 out of 5 stars 52.

February 10th, 2011: The anti-steering rule.

Four days before Apple announces that the App Store will offer subscriptions in exchange for a 30 percent cut — a controversial move all on its own — Eddy Cue and Phil Schiller codify Apple’s anti-steering rules for perhaps the very first time. “Links out of the app to purchase with other mechanisms are no longer necessary or allowed,” Schiller writes.

April 2012: Apple makes Microsoft Office use IAP.

Microsoft is bringing Office to iPhone for the very first time, and it floats the idea of cutting a special deal with Apple to share a percent of its revenue instead of using in-app purchases. Schiller tells his team: “I don’t think there is any chance we would agree with that business model. We run the store, we collect the revenue.” Office doesn’t arrive until June 2013 and winds up coming with Apple’s IAP.

January 2012: Eddy Cue shuts down the idea of featuring Shazam, then a potential competitor, in the App Store.

“No promotion... we are not going to promote something that puts it’s goal as replacing our music player unless it is significantly better than our player and this is not,” he tells App Store head Matt Fischer. Apple winds up acquiring Shazam in 2018.

December 2012: Apple rejects Google search.

The reason: “These apps need to give you the ability to use your choice of maps, not their version only.”

February 2013: Apple uses iTunes gift cards explicitly as a form of lock-in.

For Back to School, Eddy Cue suggests that Apple should bundle iTunes gift cards with new devices instead of putting them on sale — specifically to lock customers into Apple’s ecosystem and dissuade them from switching phones. “Who’s going to buy a Samsung phone if they have apps, movies, etc already purchased? They now need to spend hundreds more to get to where they are today,” says Cue.

Five months later, Apple follows through, offering $50 in App Store credit alongside new iPhones for the first time.

April 2013: Apple considers bringing iMessage to Android but decides lock-in is more important.

Eddy Cue wants iMessage on Android to hedge against Google potentially buying WhatsApp. Other top Apple execs shoot it down: “And since we make no money on iMessage what will be the point?” says Schiller. “I am concerned the iMessage on Android would simply serve to remove and obstacle to iPhone families giving their kids Android phones,” says Craig Federighi, adding, “I think we need to get Android customers using and dependent on Apple products.”

March 2016: Lock-in again kills the possibility of iMessage on Android.

“Joz and I think moving iMessage to Android will hurt us more than help us, this email illustrates why,” Phil Schiller tells Tim Cook, forwarding an email from Beats Music co-founder Ian Rogers about how he “missed a ton of messages from friends and family” after switching to an Android phone. Cook forwards the message to Eddy Cue and Craig Federighi as well.

May 2016: “Don’t feature competitors in the App Store” seems to be an unwritten rule.

“Although they may be our best and the brightest apps, Matt feels extremely strong about not featuring our competitors on the App Store,” writes Apple’s Elizabeth Lee, discussing how the company doesn’t want to highlight apps from Google and Amazon in its “Popular Apps using VoiceOver” collection.

The email thread suggests that if Apple were to feature these competing apps, it would be an exception to the rule. Lee apologies for not applying “the same filters for this collection,” and Sarah Herrlinger, Apple’s director of accessibility, asks App Store VP Matt Fischer if it would be okay to think about these apps “through a slightly different lens than most,” suggesting Apple should put its feelings about competitors aside and put the needs of customers first.

May 2018: Apple seemingly admits it manually boosted the ranking of its own Files app ahead of the competition for 11 whole months.

When Epic CEO Tim Sweeney confronts the company about why Apple’s Files showed up first when searching for Dropbox, Apple’s app store search lead suggests it was because Apple manually messed with the results. Apple now tells The Verge it was a simple mistake and there was no manual boost — but we’re skeptical, and it might be a technicality anyhow.

May 2019: LinkedIn reveals it was arbitrarily rejected for following Apple’s own example.

“LinkedIn has been rejected for using the same language on their subscription call to action button that Apple uses in our own apps,” writes Apple’s Tom Reyburn. “It’s not right, but apparently it is what it is,” replies Apple senior director of developer relations Shaan Pruden.

In a follow-up the same day, Reyburn adds: “Amazon is also complaining about this. We need to have one set of rules that all apps follow whether they are from Apple or third-party developers.”

One big question in the trial was whether Apple can and should treat games differently than other apps — and that meant calling witnesses and pulling in data from across the industry, including documents from and relating to Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo, Valve, Nvidia, Google, and Apple and Epic themselves.

Tim Cook suggested the Mac App Store needed games back in 2015; Schiller said Apple already tried.

“I think the lack of gaming (along with the lack of native productivity apps) are the main reason the Mac App Store is dormant,” wrote Tim Cook in 2015. Phil Schiller replied by suggesting Apple had already tried and failed with PC gaming — but his examples show he was completely wrong about having meaningfully tried.

He cites BioShock Infinite, Tomb Raider, Call of Duty, and Assassin’s Creed as examples, but they’re all misleading:

BioShock Infinite took five months to arrive on Mac in 2013 (not 2015), following every other major platform. Tomb Raider didn’t arrive until 2014, nearly a year after the game’s release. The Call of Duty games each took multiple years to port. And unless I’m mistaken, we haven’t seen a major Assassin’s Creed on Mac since Brotherhood in 2011 — which was months after consoles.

At least one App Store leader was well aware Mac games weren’t competitive.

In 2013, a footnote on an App Store business update presentation reads “Feral and Aspyr are porting houses that bring console/PC games to Mac. Impossible to do day/date launches given sandboxing requirements.”

Google now wants to fill that hole by bringing Android and Stadia games to Mac — and everywhere else.

In a 70-page “Google Confidential Need-to-Know” vision document from October 2020, Google reveals that it may not just bring Android games to Windows. It has its eye on Macs and smart displays, too, with a potential plan to build “the largest consumer-facing game platform worldwide, across screens,” with a “universal library” that could organize both downloadable and streaming games in a single interface.

The company’s presentation suggests Windows is just the start, and that Google could develop a “low-cost universal portable game controller” as well. The company was also apparently envisioning an attached esports tournament system and suggests “super-premium” games like Shadow of the Tomb Raider would be available on the platform — perhaps fulfilled by integration with Google’s Stadia cloud gaming service, where that game is already available.

Google’s presentation appears to be a vision document, not a concrete plan — one slide even reads “brought to you by ‘partially funded’ and ‘i have a dream’ productions.” It also suggests a 2025 timeframe.

The App Store’s 2GB limit was BioShock’d.

Remember when 2K Games ported BioShock to the iPhone, shrunk it down to fit in an impossibly small 2GB of space, and how the game got widely panned and then unceremoniously yanked from the store? Turns out, the debacle may have single-handedly convinced Apple to remove that arbitrary 2GB file size limit. “There is no reason, other than the size limit, that this 7 year old game couldn’t have looked and run BETTER on our hardware,” Apple games manager Greg Essig wrote.

Four months later, Apple announced it had increased the app size limit to 4GB.

Apple wanted a timed exclusive on Fortnite Mobile.

Epic CEO Tim Sweeney only had one condition in February 2018 before he’d been willing to fulfill that request: a service-level agreement (SLA) that Fortnite updates would take no longer than two hours to approve.

Apple didn’t agree: “I know we don’t provide an SLA — we’ve made that very clear to Epic,” wrote Apple game partnership manager Mark Grimm in a separate email chain that November, referencing how Apple had been fielding “angry phone calls” from Epic co-founder Mark Rein.

But Apple had long been interested in pushing for shorter review times, emails show. In 2014, the head of the App Store wanted “a 1 day SLA by the end of June,” even though it sounds like it continued to take longer than one day for many apps. “90% of apps get reviewed with[in] 48 hours,” wrote the head of App Review in late 2018, in response to internal fears that iOS might be “the bottleneck for cross-platform developers” like Epic, which try to push out their game updates on console, PC, and mobile simultaneously.

“If we want more games to treat us [as] a legitimate games platform, we gotta move to a more reasonable system with a shorter SLA,” wrote Apple’s head of game business development in April 2019.

Regardless, Fortnite did indeed stay exclusive to iOS for at least four months.

Fortnite wasn’t the only thing Apple wanted from Epic pre-lawsuit. It wanted Rocket League and Spyjinx, too.

When App Store VP Matt Fischer was prepping for a call with Epic in March 2020, Apple Games Business Development Manager Luke Micono sent along an executive summary that included a list of Apple’s “top priorities and asks.”

Among them: “Work together to understand the potential business impact of Spyjinx and ensure the appropriate App Store coverage for its launch” and “bring Rocket League to the App Store.” It’s unclear what will happen to these ports now that these companies have such bad blood. All of Epic’s games were pulled from the App Store in August 2020, including the Spyjinx beta. But intriguingly, that didn’t stop Epic’s subsidiary from announcing Rocket League Sideswipe, a 2D mobile game, for iOS in March 2021.

A full, 3D version of Rocket League was also coming to phones.

In a huge business presentation for Apple that also revealed a LeBron James skin for Fortnite and an Ariana Grande concert before those each became a reality, Epic revealed that it also had a second version of Rocket League in the works. This “Rocket League Next” would offer a “full game experience across all platforms, including mobile,” including crossplay and cross-progression.

It was aiming to launch a beta of the mobile game by Q2 2021, though it’s likely those plans changed: this slide was listed under “old slides” in the presentation, suggesting that Epic didn’t actually wind up telling Apple about it.

Epic CEO Tim Sweeney made Samsung a promise he didn’t keep.

“We will not ever give in to Google pressure to support Google Play, even if Google blocks Fortnite on Android, and even if the battle requires litigation lasting many years,” Sweeney told the company shortly after the August 2018 exclusivity announcement, only to eat humble pie in April 2020 when he revealed Fortnite was coming to Google Play after all.

Samsung’s response is polite, but also cutting: “I think we need to reassess the existing partnership terms to ensure that our two companies’ interests are realigned. I believe that we can come to an agreement on a more realistic partnership model going forward,” wrote Samsung Mobile president TM Roh.

That appears to have meant more money: “Samsung is already requesting a renegotiation on the rev split for both Fortnite and all other game titles,” wrote Epic in a May 2020 business presentation.

It’s also worth noting that while Roh thanks Sweeney for “letting us know ahead of time,” Epic actually put the game on Google Play the very same day Sweeney sent his email.

Microsoft believes Tencent is the biggest gaming company in the world with $20B in revenue — bigger than Activision Blizzard, EA, and Nintendo combined.

In a revealing presentation from May 2020, Microsoft revealed who it believed its true competitors are in the video game industry. China’s incredibly influential Tencent tops the list.

Microsoft didn’t seem particularly concerned about the Epic Games Store or Google Stadia yet. “We believe the store makes a minimal financial contribution to Epic’s overall business,” wrote Microsoft, and estimated that the nascent Stadia (remember, it only launched in November 2019) only made $11 million in 2019.

Microsoft estimated Sony’s PlayStation Now cloud gaming service was already pulling in $359 million in 2019.

That’s according to the same presentation as the note above. While Microsoft said it didn’t believe PlayStation Now was profitable yet, that was back when it had only around 1 million subscribers paying as much as $19.99 a month. Sony cut its price to $9.99 a month in October 2019 and announced this May that it had reached 3.2 million subscribers, so it might be profitable now.

Incredibly, you can see the entire genesis of Epic’s plan to bypass the Google Play Store in a single email thread.

“What is the feasibility of launching Fortnite on Android as a stand-alone installable program, avoiding Google Play and their 30% tax,” asked Epic CEO Tim Sweeney in February 2018.

Twenty-four hours later, the team already had a working prototype. “Here is our official plan for communicating with Google about bypassing the Google Play Store: SAY NOTHING TILL IT SHIPS,” writes Sweeney.

“We’ll need a plan for secretly negotiating bundle deals with Android OEMs with a major presence outside of China, including Samsung and LG,” he adds, “Will need to be a coordinated international effort and needs to stay below the radar.”

You’ll definitely want to read the whole email thread when you get a chance.

Sweeney was inspired by how Tencent got around Google Play with its WeChat app.

“This is exactly the process Tencent followed to bypass Google Play with WeChat, which they soon opened up as a game distribution platform. The sooner we can free ourselves from the App Store distribution monopolies, the better,” wrote Sweeney.

Epic offered to bring Fortnite to Google Stadia — if Google gave Fortnite a free pass to the Play Store on Android, too.

“Apparently Mark R had a meeting with Google Play. His offer “Put Fortnite launcher in GP for free, we will give you FN on Stadia,” one Epic employee texted another in August 2019. (Both names were redacted.)

But in July 2020, Epic CEO Tim Sweeney opted not to mention that dangling carrot when asked why Stadia didn’t have Fortnite yet:

There’s not a deep reason. We fully support Stadia in Unreal Engine however the effort required to release Fortnite updates weekly in sync across 7+ platform is extreme and that makes it hard to add platforms that don’t yet have mass market user bases.

— Tim Sweeney (@TimSweeneyEpic) July 28, 2020

As for why Fortnite isn’t available in Microsoft’s Xbox Cloud Gaming service, Epic’s Joe Kreiner admitted that it’s deliberately withholding the game from a platform it sees as a competitor. That’s despite bringing the game to Nvidia’s GeForce Now and a plan to offer it in Walmart’s unannounced cloud gaming service, codenamed “Project Storm,” which was also revealed in Epic’s confidential emails. “Bottom line is there’s a huge potential for wringing more Fortnite sales out of Walmart especially if we support their efforts on this,” argued Epic co-founder Mark Rein.

Epic’s idea of springing a legal trap predates the fight with Apple. It goes back to when Epic tried to evade paying Google a percentage of sales and still return to the Play Store.

“[T]he goal is draw Google into a legal battle over anti-trust,” wrote Epic marketing director Haseeb Mailk in a September 2019 email. “If we are rejected for only offering Epic’s payment solution. The battle begins. It’s going to be fun!”

But Epic never got to announce its strategy in 2019. That plan was thwarted when the idea leaked to 9to5Google that Epic would ask for a “special billing exception,” a notion that Epic rejected in a statement to The Verge. Google responded by pointing out that Epic hadn’t tried to dodge Apple’s 30 percent fee. Apparently, Epic took that to heart, laying a trap for both Apple and Google with its #FreeFortnite campaign in August 2020.

The Coalition for App Fairness (CAF), an advocacy group nominally founded by Epic, Spotify, Tinder’s Match Group, and 10 other developers, appears to have actually been created and funded by Epic explicitly to help win its case.

“We have employed the firm who can run the strategy for us and build the coalition for us,” wrote Epic marketing VP Matt Weissinger in a May 2020 email, noting that it would take “$80K - $100K to get the coalition funded.”

And while a copy of an August 2020 contract between Epic Games and a Messina consulting group suggests that the new 501(c)(4) organization will be “separate and independent from Epic,” it also specifies that “the day-to-day operations will be managed by the Consultant with direct reporting into Epic’s head of marketing.”

The May email mentions a “Lane” — that may be Lane Kasselman, a crisis communications specialist who put together an extensive presentation on strategies to sway journalists and public sentiment, including a coalition. An Epic Project Liberty presentation from July explicitly says Lane Kasselman’s Greenbrier will “help manage the organization” and work with it to “develop research to help establish our position,” and that Epic expected to spend between $400,000 and $700,000 over the life of the coalition.

The Coalition for App Fairness and several other founding members tell The Verge that the organization is certainly not under Epic’s thumb now; Spotify says the CAF was not launched until after it had drafted a set of principles, including an explicit decision not to include litigation like Epic v. Apple in its business, and members say the CAF reports to its board of directors, where Epic has a single vote.

But Epic would not confirm or deny whether it provided the original funding, hired a consultant to form the group, or bound that consultant to report directly to Epic, after repeated requests, and no CAF member we contacted would comment on that.

Correction: We typo’d: Spotify said the CAF originally decided to exclude, not include, litigation from its ongoing business.

If Fortnite’s numbers are representative, Europe prefers PlayStation to Xbox by a four-to-one ratio.

While it’s not surprising to think that the Xbox would be more popular on its native continent— it was famously a nonstarter in Japan — I don’t know if I’ve ever seen graphs showing a staggering disparity like this.

Last August, Epic CEO Tim Sweeney gave Microsoft Xbox chief Phil Spencer a cryptic heads-up about #FreeFortnite.

Sweeney hinted at “an extraordinary opportunity” to boost consoles and PCs at mobile’s expense and suggesting he make Fortnite multiplayer free to play on Xbox without a subscription.

While Microsoft didn’t wind up dropping the Xbox Live Gold requirement for free-to-play games until this April, it did arguably come to Epic’s aid during the Epic v. Apple trial with exhibits and testimony.

Microsoft Xbox chief Phil Spencer is still trying to bring the company’s cloud gaming service xCloud to other consoles.

Or so he told Epic CEO Tim Sweeney two days after the previous email.

Does that mean there were negotiations to bring it to Nintendo Switch, perhaps, or PlayStation? Sony and Microsoft do have a cloud partnership, and Nintendo teamed up with Microsoft to push Sony on crossplay not that long ago.

Speaking of crossplay: Sony and Epic were already quietly testing crossplay in January 2018 with both Fortnite and Paragon, and negotiating for much of that year.

In March 2018, Epic and Microsoft publicly revealed that Sony was the only thing keeping every single Fortnite player from being able to play with friends across platforms — but behind the scenes, Epic and Sony were in active discussions to make cross-platform a reality, according to the companies’ emails.

As we’ve written, things got heated. Epic tried to strongarm Sony into enabling crossplay between PS4 and Xbox, with Epic VP Joe Kreiner saying, “I can’t think of a scenario where Epic doesn’t get what we want — that possibility went out the door when Fortnite became the biggest game on PlayStation” in early March. Sony wound up demanding extra financial assurances before it finally caved in September 2018.

But we can also now see moments where Sony and Epic were on better terms. Did you know the companies quietly launched PS4 to PC crossplay in January 2018, two months before the shit hit the fan? Epic shared the results of that test with Sony in February. “We’d like to get the existing Paragon/Fortnite PC exceptions extended to iOS and Android quickly,” Kreiner told Sony developer relations head Phil Rosenberg, adding that “Epic will publicly push that we have crossplay PS4/PC” once Sony agreed to open cross-platform voice chat as well.

Another email thread in June shows Epic CEO Tim Sweeney taking a hard tack on adding Microsoft just days before E3 2018 — with phrases like “Frankly, we do not believe Sony’s position is even legal” and the ultimatum “Please inform Kodera-san, and please be clear that Epic will enable full interoperability between all platforms in Fortnite at a timely point in the future.” But Sweeney goes on to apologize, too, as you can read for yourself in the document above.

In a March 15th “exclusivity and co-marketing agreement,” we can see that Epic traded away something else to get crossplay, cross-platform DLC and cross-platform voice chat across PS4, PC and mobile, too. It agreed to bake Sony’s PS4 tournament platform APIs into Unreal Engine 4.

Sony and Epic’s legal agreement continued to evolve: after adding Xbox crossplay in September 2018, the parties added Linux to the list of “permitted platforms” in May 2019 and then added Google Stadia in September 2019. But Tim Sweeney decided to hold Stadia for ransom, as I mentioned earlier.

Nvidia’s GeForce Now cloud gaming service almost snuck onto the App Store.

On August 19th, 2019, the same day Nvidia announced it for Android phones, Apple “erroneously approved” the cloud gaming app for iOS and only realized it shortly before the app was set to go live.

Six months later, Nvidia told us there were no plans for iPhone or iPad support, but in November 2020, it arrived as a web app, with Fortnite in tow.

Epic pushed Sony to offer recurring subscriptions at the same 15 percent rate as Apple and Google so it could “save hundreds of millions” on fees.

In September 2018, Epic staffers suggested they should bring it up during a visit to provide input on the upcoming PS5. Sony told Epic “we’re thinking about it,” according to an unnamed Epic staffer.

As far as we’re aware, this never changed. Generally, Sony, Microsoft, and Nintendo take 30 percent of games sold on their platform. Apple’s 15-percent-after-one-year subscription rule dates back to 2016.

Vietnam demanded that Apple remove Fortnite from the App Store in September 2018.

“We cannot in good conscience obtain the Vietnam ABEI license as Apple asks,” Epic CEO Tim Sweeney replied to Apple, explaining that Vietnamese law would require placing some Fortnite servers under the control of the communist government. Apple approved of this stance and agreed to pass the buck unless the Vietnamese government forced it to take action — and as far as we can tell, Fortnite was never removed from the App Store in Vietnam.

Tim Sweeney apologized profusely to Ubisoft after The Division 2 was suddenly and mysteriously snapped up by fraudsters with stolen credit cards on the Epic Store.

It sounds like it didn’t last for long, but it might have raised some eyebrows in April and May 2019:

In a separate internal email thread, Epic reveals its mistake: when thieves bought Epic Game Store games with a stolen credit card, Epic didn’t have any way to keep them from reselling accounts loaded with those games. “Fraudster creates uplay account, uses stolen CC to purchase The Division, and then sells the account. While Epic account gets disabled by chargeback, without clawback with Ubisoft the game is still available on uplay and sold account works,” Epic’s Daniel Vogel explained.

Ubisoft told Epic it had sold 118,865 copies of The Division 2 by that point, of which roughly 10 percent (11,624 copies) had been returned. Seventy percent of those (8,185) were fraudulent refunds, mostly located in the United States, according to the email chain.

Epic negotiated with Apple to take over the App Store in late 2019 to promote Fortnite Chapter 2.

It’s not not clear what Epic offered, but if you’ve been wondering whether Apple’s App Store suggestions are wholly curated, the answer is a definite no. “We will also be given creative control on what we want to display and how,” wrote Epic marketing director Haseeb Mailk, roughly two weeks before Fortnite’s black hole closed.

Epic quietly tested reducing its Fortnite prices in Denmark before it sprung the Project Liberty trap.

Epic argued in July 2020 that by bypassing Apple and Google’s cuts, it could pass the savings along to consumers with 20 percent lower prices on mobile platforms. But first, Epic decided to find out what it had to lose — and a quiet test in Denmark showed it might lose 10.8 percent on average per day, per user, for a projected impact of $234 million.

Epic argued the future of augmented reality was at stake in its legal fight.

In a presentation to Epic’s own board of directors in July 2020, the company listed four reasons why Epic believed “the time is now” to fight Apple and Google. “Solve this problem before AR takes off and that rate is set at 30%” was one of them.

The top reason was redacted, but the other two were “Fortnite’s all time high user base plus the Marvel Season and concerts add pressure to Apple and Google” and “Growth is predicated on user generated content; stronger creator revenue share from lower mobile platform fees.”

Nintendo doesn’t allow its Japanese game partners to work with the Yakuza.

Seriously! It’s one of the very few things we’ve learned about Nintendo from court documents.

The App Store might largely be “a safe and trusted place to discover and download apps,” like Apple advertises on its homepage. But it’s also a place where egregious scams can go unchecked. The Epic v. Apple trial revealed the company has long known it has a bad app problem, with employees sometimes identifying entire categories of app that harbor fraud — and yet, the company fails to consistently take lasting action.

July 2011: Former App Review lead Philip Shoemaker takes part of his team to task after multiple fake Flash video players get approved.

Shoemaker writes: “[T]hese apps are all misleading, have always been misleading, and there’s no way the reviewers actually checked to see if the app did what it said it did. This means we are not truly checking for core functionality, are we?” He suggests this type of app shouldn’t make it into the store, period.

February 2012: “This is insane!!!!!!!”

Phil Schiller goes on a rant: “How does an obvious rip off of the super popular Temple Run, with no screen shots, garbage marketing text, and almost all 1-star ratings become the #1 free app on the store,” adding, “Is no one reviewing these apps? Is no one minding the store? This is insane!!!!!!!”

October 2013: Plastic knife, meet gunfight.

Eric Friedman, now head of Apple’s Fraud Engineering Algorithms and Risk (FEAR) team, says the company’s App Review team is “bringing a plastic butter knife to a gun fight,” a spicy quote you may remember from the trial. It seems that quote was in response to a rather simple scam: Chinese apps requesting that their users give them 5-star reviews, which the App Review team apparently wasn’t catching.

July 2014: Apple was aware of enterprise certificate app fraud years ago.

In February 2019, we wrote how Apple’s iOS has a seedy underbelly that allows gambling, porn, pirated games, and more onto the iPhone, using enterprise certificates. Apple said it would be more proactive following the reports — but emails released during the trial show it knew about this years ago.

Five years earlier, in a July 2014 thread explicitly titled “Black Market App Store Follow-up,” Friedman is well aware and says he’s been tracking the “EPP exploit” for months. “You can redistribute the entire store if you’re able to convince your customers to install and trust your certificate, which millions of people are apparently willing to do,” he explains to colleagues.

“We really need to get controls in place on the EPP on boarding process if we want to put a stop to this,” writes Friedman.

March 4th, 2015: Apple top brass decide to boot an antivirus app off the store with very thin justification.

“Phil was adamant that these antivirus apps were misleading: viruses do not exist in ios so they are misleading even in the case where they are scanning attachments for other platforms,” writes Shoemaker, after Intego’s VirusBarrier gets removed from the App Store. “I sort of get Apple’s point,” writes Intego CEO Jeff Irwin at the time, who also suggests in a blog post that his competitors might be affected as well.

Six years later, the App Store is filled with antivirus apps, including some rather shady-looking ones — but Intego’s VirusBarrier has not returned.

March 27th, 2015: “PLEASE develop a system to automatically find low rated apps and purge them!!”

Phil Schiller instructs the App Store team to develop a system to find and purge low-rated apps, after Tim Cook forwards him an email about a scammy wallpaper app that tricks the user into giving it a 5-star review. It’s not clear Apple ever did this, and scam app hunter Kosta Eleftheriou recently found another app that forces users to give it positive reviews.

September 2015: Apple knew that auditing its own user reviews of apps could help.

In the margins of an internal Apple presentation for “Columbus,” a project designed to improve the quality and consistency of App Review, an Apple employee identified simply as “Matt” notes that the company needs to continue to audit its catalog for scams because there are a “ton of scam apps in the store” that are called out in their own reviews.

That’s still a problem in 2021. In April, Apple wouldn’t even tell us whether it goes back to inspect the App Store’s most lucrative apps for fraud.

September 2015: The XcodeGhost malware that hit iOS in 2015 impacted far more Apple customers than initially suspected:

128 million of them across 2,500-plus different apps. While Apple went on to email every affected customer, it didn’t publicly reveal the scope of the impact, originally just estimated at a few dozen Chinese apps, including WeChat.

Turns out China only accounted for just over half the affected customers, too: “As you can see, a significant number (18M customers) are affected in the US,” reads an internal email forwarded to executives.

January 2016: Friedman bad-mouths App Review again.

“Regarding review processes: please don’t ever believe that they accomplish anything that would deter a sophisticated attacker. I consider them a wetware rate limiting service and nothing more. Yes, they sometimes catch things, but you should regard them as little more than the equivalent of the TSA at the airport. Their KPI is ‘how many apps can we get through the pipe’ and not ‘what exotic exploits we can detect?’”

November 2016: Headspace gets special treatment after complaining about scams.

The CEO of popular meditation app Headspace complains directly to a contact about scam apps stealing its branding, screenshots, and description: “Shockingly, Apple are approving these apps, and when the users buy the apps they are left with nothing but some scammy chat rooms in the background.” Within an hour, he’s speaking to the head of the App Store via email, and is on the phone with the head of App Review within two weeks, according to the email thread.

June 2017: “How to Make $80,000 Per Month on the Apple App Store” postmortem.

Following a damning Medium blog post about “How to Make $80,000 Per Month on the Apple App Store” by getting a scam atop Apple’s Top Grossing charts, Friedman prepares an internal presentation identifying a wide variety of reasons why those scams worked — and some suggested solutions, like flagging suspicious price changes for review, making it far easier to cancel a subscription, flagging apps with high cancellation rates, even eliminating entire categories of bad apps like antivirus software from the store.

It’s possible Apple pursued some of these mitigations, but, again, it didn’t stop high-grossing scams from proliferating on the App Store years later.

October 2017: Pretty lady versus drug-sniffing dog.

Friedman is frustrated with how Apple’s App Review process is still letting scams through: “As much as those guys want to help, their paycheck depends on getting apps in the door and keeping developers happy. They are more like the pretty lady who greets you with a lei at the Hawaiian airport than the drug sniffing dog who, well, never mind ;)”

There’s more to the full email, though. In a February 2018 reply, Herve Sibert hints at another worrying practice at Apple we’ve covered in the past: manipulating search results to achieve the company’s desired effect. “Just like in October, AppReview fails to review properly, and we just tamper with search results (which could be dangerous from a legal perspective) to try to correct,” laments Silbert, pointing to a TechCrunch story about a knockoff app in China where, it now seems, Apple may have resolved the issue by artificially boosting the ranking of the original app.

January 2018: “This PDF is shocking, lots in here”

“This PDF is shocking, lots in here,” writes App Review chief Trystan Kosmynka. “We need to think about how to stop this from happening. We also need to quickly consider how to go about finding any of these scams that are live and figuring out how to take action,” he adds, in response to a 32-page slide deck titled “How to make $500k/Month by scamming Apple’s App Store’s Users.”

The presentation explains how a brand called Holy Grail managed to trick users into paying $40 a month each for ringtones, wallpapers, horoscopes, and bible messages they harvested off the internet for free, pushing users into a fake free trial, overwhelming the app’s actual negative user reviews with fake 5-star ratings, and hoping Apple would never look at user reviews that correctly identify the scam. In other words, the same tactics that scam hunter Kosta Eleftheriou, we at The Verge, and The Washington Post discovered were still polluting the App Store years later.

May 2018: Apple realizes, seven months late, that it approved two school shooting games.

“So far all evidence points to Armin was going too fast and missed all the signals to reject these apps [...] it took a total of 32 seconds to approve both apps,” reads part of a postmortem thread.

October 2018: Apparently, Apple didn’t quite have someone in charge of App Store fraud until now.

“I need you to take leadership regarding what’s going on with all forms of fraud on the App Store and have someone on your team focus on this,” App Store VP Matt Fischer tells Pedraum Pardehpoosh, a director of product management. This comes after Ricardo Cortes, who leads the App Store’s back-end tools, suggests that the problem has gotten serious — with “material business justification for the amount of fraud that’s occurring on our storefronts, especially in China.”

“So we believe there is a big impact for both developers and customers,” Cortes adds.

February 2019: A fake blood pressure monitor app makes it to No. 12 in the App Store’s medical category.

“The app is still nonsense and should not be on the store,” writes Kosmynka, after it comes to light. “The app claims to detect blood pressure using the camera from a finger tip. This is not possible at the moment,” writes a tipster whose name is redacted. Apple removes it from the store.

But if it’s true that this entire idea is a scam, Apple doesn’t seem to have done much about it since. You’ll find plenty of apps that claim to detect your blood pressure this way on the App Store right now — including ones with “free trials” that trick you into an expensive auto-renewing monthly subscription.

June 2019: One possible reason why the App Store has inconsistent enforcement: long hours and high quotas.

In an internal fact-check for this CNBC story, Apple admits its app reviewers typically work 10 hours a day, five days a week, and typically review between 50 and 100 apps each day — except when App Review needs to catch up and offers 12-hour days instead.

At Apple’s current 2021 totals of 500 app reviewers and over 100,000 apps processed each week, a reviewer working 10-hour days would average only 15 minutes per app — if they worked without taking any breaks.

August 2019: Apple realizes it’s failed to squash fake heart rate apps.

Eight months after scam apps emerge that trick users into placing their finger on the Touch ID sensor — promising to sense their heart rate but instead charging them loads of money by using their fingerprint as instant verification — a developer manages to sidestep Apple’s ban and do it all over again. “The team has been investigating this and I’m expecting a writeup shortly,” writes Kosmynka, perhaps a little too late — it’s after he’s been sent a copy of this 9to5Mac story.

November 2019: The App Store has a fraud team now.

By this point, it appears that App Review does indeed have a fraud team of its own, called App Review Misleading Fraud (ARMF) as well as three other divisions: “Technical Investigations (TI),” “App Store Improvements (ASI),” and “App Review Compliance (ARC).” That’s according to an Apple email about a slight re-org for those groups.

February 2020: Apple’s head of fraud suggests Apple may be unwittingly providing “the greatest platform for distributing child porn.”

Halfway through an iMessage conversation about whether Apple might be putting too much emphasis on privacy and not enough on trust and safety, Friedman comments that “we are the greatest platform for distributing child porn,” adding that “we have chosen to not know in enough places where we really cannot say” and referencing a New York Times article where, he suspects, Apple is “underreporting” the size of the issue.

He also shares a slide from his upcoming trust and safety presentation where “child predator grooming” is listed as a known issue for the App Store and iMessage. This August, Apple revealed a controversial plan to try and fix that, including scanning photos on device to see if they match known child sexual abuse material before uploading them to iCloud.

June 2020: Phil Schiller goes “WTF” when a protester shooting game makes it onto the iPhone.

Schiller forwards an email about how the App Store now contains a game that allows players to shoot cannons at protesters, amid the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests and ongoing police brutality. App Review head Trystan Kosmynka replies: “App has been removed, looks like it was approved prior to current events, still not okay as this would never be an appropriate concept.”

One of Apple’s most self-serving rules is also one it didn’t originally write down — the one where it doesn’t allow other companies to create another catalog that lives inside its own. It’s how Apple originally tried to exert dominance over ebooks and, more recently, how it kept cloud gaming services like Google Stadia and GeForce Now at bay. But Apple hasn’t always been forthright and consistent about applying this rule.

August 2011: Apple’s Executive Review Board rejects Kobo’s ebook app for being a store.

“Clearly a store, even has pricing,” Apple writes. It also rejects an app called “The Web Store,” writing, “We do not want apps that replace our store with web apps.”

November 2011: “I have no guideline to remove their app on, but have been asked by the ERB to hide it. I will be doing so immediately.”

That’s what App Review chief Philip Shoemaker writes, after Big Fish Games successfully publishes a streaming subscription game service to the store.

“I honestly don’t know what we’re going to say to this developer other than ‘We don’t allow App Stores within an app in our App Store,’” Shoemaker adds, telling PR director Tom Neumayr that “its chickenshit. We don’t have a guideline for this.” Apple yanks Big Fish Games that same day without any explanation.

December 2012: Apple’s Executive Review Board rejects a WeChat update because it contains embedded games.

WeChat, now practically a Chinese internet unto itself encompassing social networking, chat, shopping, payments, and yes, games, temporarily falls afoul of Apple’s unwritten rule. “[T]his is a clear store within a store, or app distribution play, and is not allowed,” Apple writes (on page two of the PDF linked below). But somehow, games come to WeChat anyhow a year later without being rejected by Apple, and slowly spread globally.

February 2013: Apple admits it still doesn’t have grounds to reject another Big Fish update.

Two years later, Big Fish is still trying to get approved, and Apple still isn’t having it, continuing to cite a rule that doesn’t actually exist. “Big Fish Unlimited is seen as a game store within an app. This is not allowed. Phil and Eddy have been adamant about this, despite my protests. We have no clear guidelines around this,” writes Shoemaker.

September 2013: By appealing to Tim Cook, a sheet music study app gets past the rule.

It seemed as though KnowledgeRocks’ synchronized sheet music study app would never make it onto the App Store after months of rejections for being a store within Apple’s app store, but after emailing Tim Cook “in desperation” on September 4th, it appears that Apple approved it a week later. In a 2014 YouTube video, it appears to have in-app purchases for each piece of music.

July 2017: Apple realizes years later that it let Roblox slip past, too.

Roblox was nearly rejected for containing a store within a store, according to an email investigation by App Review senior director Trystan Kosmynka several years later. It might not have been approved — if not for the fact that Apple’s Executive Review Board didn’t manage to have a successful meeting on the day Roblox came up for review.

August 2017: Apple rejected cloud gaming platform LiquidSky using the rule.

“LiquidSky submitted a working version of their client to the iOS App Store but it was rejected by App Review due to it being a ‘sub app store’ since they allow games purchased elsewhere to run on their platform,” reveals Apple VP John Stauffer, as he attempts to convince Craig Federighi that Apple should buy the company. Federighi shoots it down for many reasons (which you can read below). Walmart winds up purchasing LiquidSky in 2018 to become the backbone of its unannounced cloud gaming service.

March 2018: The Tribe video chat app gets retroactively pulled after adding games, even though Apple knows it let similar apps through.

Apple explains internally that it’s yanking the Tribe video chat app for being a store-within-the-store now that it has added multiplayer games you can play alongside your chat. “They are a live multiplayer games platform which we do not allow,” Apple’s Bill Havlicek adds. (Founder Cyril Paglino asks whether WeChat, Facebook Messenger, and Roblox will be getting banned for their bundled games, too.)

A few months later, Pagalino tells VentureBeat that he had to shut down the app due to Apple’s rejection.

Originally, Apple’s in-app purchases were optional — something developers actually asked for. “[Steve Jobs] has agreed to do in-app purchases for Kirkwood,” wrote iOS chief Scott Forstall in December 2008, roughly 10 months before the company officially announced its In-App Purchase API for all developers. But over the years, as the vast majority of lucrative apps on the store have become free to try, IAP has become the primary way Apple profits from the store — and sometimes, the way it forces developers to pay up.

Here’s a handful of examples where Epic shows that Apple isn’t applying the toll fairly.

June 2011: Apple placates Netflix and Hulu.

Apple creates a new App Store rule that lets them avoid paying the standard Apple tax by selling subscriptions on their websites instead of using in-app purchases — and tells them about it ahead of other devs. It’s now commonly known as the App Store’s “Reader” rule. “They were both pleased with this,” Eddy Cue tells the App Store leadership team.

April 2012: Google Drive and Microsoft SkyDrive may have triggered a wave of retroactive IAP shakedowns.

When Apple realizes it rejected Google’s cloud storage app for not offering in-app purchases, but approved Microsoft’s cloud storage app despite it lacking them, too, Apple’s Tom Reyburn proposes a “fair” solution: getting every other major cloud storage provider to retroactively add IAP, too, and giving them a deadline for compliance. “I’d like to be proactive in getting these developers in line,” he writes.

January 2016: Apple software developer Panic skewers the Apple tax.

While not exactly railing against the 30 percent fee, Panic CEO Cabel Sasser pens an email including this quote: “the App Store takes parts of our job that we’re already extremely good at — like customer support, quick updates, easy refunds — and makes them all more stressful and difficult, in exchange for giving Apple 30% of our revenue.”

Panic has slowly retreated from Apple’s official App Stores for years now, most recently discontinuing its Code Editor for iOS in May. The company also recently created the Playdate, a unique crank-powered gaming handheld.

May 2017: Apple threatens to reject an update for Minecraft: Apple TV Edition.

After Apple discovers that the game’s new Marketplace feature won’t let players buy Minecraft coins without logging into a Microsoft account first, it demands Microsoft update both the TV app and its already-approved iOS version of Minecraft to change that. Microsoft immediately agrees to fix both, according to Apple’s internal emails — with the understanding that users can now bring their existing currency to Apple’s platforms.

February–July 2018: Apple loses a game of chicken with Netflix.

When Netflix becomes unhappy with how many Apple users are canceling their subscriptions, it proposes (and then seemingly demands) to turn off in-app purchases in 11 countries as a test, a move that would deprive Apple of its fee.

But instead of immediately threatening to take action, Apple entertains the idea for several months, working with Netflix on specifics. In May, Apple’s Eddy Cue and Matt Fischer direct the team to pull all marketing for Netflix around the world, with Fischer writing, “We want them to feel the pain.”

But by July, Apple is discussing what kinds of special treatment would entice Netflix to stay. Netflix runs its test in August and drops IAP entirely in December, seemingly without any new consequences from Apple.

June–December 2018: Apple tries to push Uber and Lyft into IAP but seemingly caves.

While Phil Schiller told the judge in Epic v. Apple that Apple doesn’t take a cut of physical purchases and physical delivery services like Uber, Lyft, Instacart, and Postmates, that wasn’t always the plan: Apple decides in June 2018 that “Membership Subscriptions” should become “a sizable new revenue stream,” specifically as a way to make money from the companies named above. “We believe Membership Subscriptions can become a key lever to monetize some of the most popular free apps,” writes App Store business lead Sheree Chang.

In July, Apple explicitly tells Uber it would need to figure out how to pay the Apple tax. “As we expected, they balked at the 30% rev share,” writes Chang, “As our conversation continued, they seemed to start accepting that they would likely need to pass the 30% along to the consumer.”

But on October 30th, Uber blindsides Apple by launching its Ride Pass monthly subscription without IAP anyhow, according to another email thread.

It’s not clear what happened right afterward, but it seems that Apple caved: in December, Apple tells Lyft and Uber that IAP would be optional, according to the emails. “Unfortunately, IAP being ‘optional’ means that no one will ever use it,” writes App Store VP Matt Fischer, suggesting the company still needs a “next approach that will work for us and our developers.” Today, Uber’s iOS app only accepts credit cards, debit cards, or PayPal when signing up for a subscription.

October 2018: Apple realizes that Hulu is sneakily switching subscribers away from Apple’s in-app purchase system.

Hulu is abusing a “subscription cancel/refund API” that most developers never had access to in the first place. More info and email snippets here.

January 2019: Match Group tells Apple “we’re driving almost 100% of the revenue growth for you” while asking to skirt the standard 30 percent Apple commission.

Match argues that its dating subscribers don’t stick around long enough for Apple’s 15-percent-after-one-year reduction to kick in. “As a top grossing partner, we never are able to take advantage of the 15% rev share since the intent of our apps is to actually have people meet and leave our apps,” Match argues. This argument apparently does not work on Apple, as Match goes on to publicly criticize Apple and join the Coalition for App Fairness. Match also bypasses Google’s Play Store cut.

June 2020: Here’s what happened a day after Apple’s controversial decision to strongarm the Hey email app into adding in-app purchases.

“I think we should stand by our guidelines and explain them. Quickly,” writes Phil Schiller on June 17th. Apple’s corporate communications team suggested that Apple should respond by either approving the app and working on the details or by sending a “thoughtful letter” to Hey explaining Apple’s stance — with the caveat that “Apple will be seen as ‘doubling down’ and a letter will not placate the developer.” The Verge’s headline the following day: “Apple doubles down on controversial decision to reject email app Hey.”

Did Epic actually have a lot to lose when Apple pulled Fortnite off the App Store? It doesn’t seem so — according to confidential emails and data revealed during the trial, it might have been a relatively easy choice.

As of March 2020, mobile only accounted for 6.58 percent of Fortnite’s revenue, and less than a tenth of the game’s daily active users.

You can see actual download and revenue numbers for each platform here, too, which shows consoles were the true cash cow.

And that was near the peak: according to Epic’s own monthly user data (as plotted by an Apple expert), iOS numbers had been declining since April, months before Apple pulled the game.

Android numbers have consistently stayed low, too, with little improvement even after Epic’s public stunt.

According to the data, PS4 was responsible for 46.8 percent of Fortnite’s $10.6 billion in revenue between March 2018 and July 2020 — nearly half. And 27.5 percent was Xbox One, 9.6 percent was PC, and 8.4 percent was Nintendo Switch, leaving iOS with 5 percent and Android with a measly 0.6 percent.

For many players, the iPhone app might just have been an easier way to buy their V-Bucks.

Epic e-commerce lead Wen-Jen Chang shared an interesting theory in September 2018: while “most players are still playing on PC/Epic platform as they did before,” they were now buying their V-Bucks on mobile platforms. “It seems that PC/Epic ecom may have been impacted most by the additional of these platforms,” he said.

The data does suggest iOS users didn’t actually play there a lot:

While iOS had the largest number of Fortnite accounts of any platform at 115 million, iOS also only accounted for just 4.4 percent of all Fortnite playtime through July 2020, according to an Apple expert’s accounting of Epic’s numbers.

And while that might largely be people briefly trying Fortnite on iOS and never picking it up again — iOS users spent 89.8 percent of their Fortnite playtime and 86.8 percent of their money somewhere else — the iPhone and iPad did reportedly account for a slightly disproportionate share of spending. 7 percent of all Fortnite revenue came from iOS, a bit higher than the 4.4 percent of playtime. That said, only 8.4 percent of iOS Fortnite users actually made a purchase on iOS, with 15.8 percent of iOS users buying somewhere else, and 75.9 percent of iOS users never paying at all.

Either way, iOS and Android were a gateway for new players.

While iOS and Android only had 6 percent and 4 percent retention rates as of March 2020 (compared to 21 percent for Switch and 16 percent for PS4), Epic wrote that mobile drove 38 percent of new Fortnite user accounts in 2019 and that 15 percent of mobile players go on to try it on console.

Epic approached nearly every Android phone manufacturer to preinstall Fortnite — and it gave Samsung 12 percent of its revenue there.

No other phonemaker got a cut, but it also offered cellular carriers Verizon, Telefonica (O2, Movistar), and Hutchison (Three, Windtre) a 5 percent share of Fortnite purchases when customers tacked them onto their phone bill.

Telefonica’s Movistar took Epic up on that offer, launching carrier billing last June.

Despite the OEM and carrier partnerships, Fortnite on Android is scrambling to make a dent against competitors like PUBG Mobile and Call of Duty.

With lifetime revenue of just $45M as of March 2020, the Android version of the game was less than a tenth of even the iOS business, and Epic has page after page exploring why in a “Mobile Business Update” you can read below — including how the game’s high system requirements lock out billions of users, how people get lost in the complex series of steps it takes to install Fortnite, and how the huge download sizes meant Fortnite could easily take 10 minutes longer than competitors to load.

You can see Fortnite’s entire budget for the first nine months of 2017, right before it released the now-dominant Battle Royale mode to the world.

It confirms that Epic had a Project Athena, previously rumored to be the codename for Fortnite’s battle royale mode before it eclipsed the original game, and it shows just how much Epic paid its own staff and an army of contractors to outsource various elements of development.

And you can see Epic’s entire 2018 and 2019 P&L and forecasts for 2020 — including how Fortnite made a staggering $9 billion in its first two years.

Other Epic games were a blip at just $108 million, with the Unreal Engine making $221 million and the Epic Game Store pulling in $235 million during that same two-year period.

Epic revealed some rare Unreal Engine numbers, too.

At the end of 2019, Epic revealed in a confidential email that it had 320,000 monthly active users of the Unreal Engine, 9.7 million downloads, and over a quarter of its roughly 2,000 employees worked on the Unreal Engine team. Those numbers aren’t directly comparable to the ones competitor Unity revealed in its S-1 filing last year, though, and Epic revealed during the trial it actually has 3,200 employees now.

Epic paid just $11.6 million to shower its Epic Games Store users with free games, and it totally drove adoption.

As we’ve reported, the company’s strategy of giving away free games every week gave the company 18.5 million new users in the store’s first year, in exchange for a simple one-time “buyout” fee. Epic paid as little $45,000 for Tequila Works’ Rime, or as much as $1.5 million for the Batman Arkham trilogy which attracted over 600,000 new users by itself.

A massive September 2020 presentation reveals practically everything you’d want to know about the early days of Epic’s Steam competitor.

The Epic Games Store raked in an average of $17.5 million across its first 14 months, with a low of $1.5 million in January 2018 and a high of $72.6 million in September 2019, falling back down to $11.4 million last February, with its 10.14 million daily active users that month spending an average of $1.12.

Grand Theft Auto V enticed over 7 million users to try the Epic Games Store.

Epic had its single biggest day in Epic Games Store history on May 14th, 2020, when it made GTA V free to claim, with over 7 million people either signing up for an account or taking their first action on the Store that day. Epic saw over 15 million daily active users on the store that day, too — despite an eight-hour outage that we covered at The Verge.

It was only the company’s second biggest sales day, though, grossing roughly $6.5 million. The biggest was the launch of Borderlands 3, when Epic grossed $14 million in one day — though Epic had to pay 10 times that to secure PC exclusivity.

Epic paid $146 million to secure PC exclusivity for Borderlands 3, its biggest Epic Games Store launch yet.

That includes a $15 million marketing commitment, $20 million in “non-recoupable fees,” and an $80 million minimum sales guarantee that it did recoup in the first two weeks of sales. But Borderlands 3 only reached $91 million in sales by the end of the year, according to a September 2020 presentation.

Epic offered $200 million to Sony to bring “4-6” of its PlayStation games to the PC game store, and Epic was approaching Microsoft, too.

We wrote about this earlier, but the September presentation reveals that Epic was ready to spend big bucks to bring console content to PC, though it doesn’t seem to have been successful: Horizon Zero Dawn and Days Gone appeared on both Epic and Steam. But it’s possible Epic’s cash helped convince Sony to move in this direction. In May, we spotted that Uncharted 4 is coming to PC, too.

The presentation states that Epic was in “opening conversations” with Microsoft, but that Xbox chief Phil Spencer was also “occasionally” meeting with Epic’s chief rival: Valve’s Gabe Newell.

Paradox Interactive was holding out for an Epic amount of money.

In September 2019, Epic emailed its board of directors to suggest an investment in Paradox, including an undisclosed amount of upfront cash in the form of a minimum sales guarantee, in exchange for its entire back catalog, an exclusive on a hotly anticipated strategy game sequel, and the possibility of “walking away from their business on Steam to come here,” according to Epic emails.

That would have likely been Crusader Kings III, which our sister site Polygon called one of the best games of 2020 and “an epic that breaks free of the strategy game genre entirely” when it arrived on Steam and Xbox Game Pass — but not Epic — last September. Epic described the unnamed title as one that “appeals to an even wider PC strategy audience [...] based on the advancement of the mechanics + change in context” and given that Paradox hasn’t released any other big games between September 2019 and now, that seems about right.

While an exclusive deal could have been an Epic coup, Tencent executive and Epic Games board member David Wallerstein seemed cool on the idea in the email thread, Epic CEO Tim Sweeney admits that “Obviously, the direct ROI scenario here is super crappy,” and it doesn’t appear to have happened.

Epic believed it could claim half of all PC gaming revenue if it kept paying for Epic Games Store exclusives — assuming “Steam doesn’t react.”

In the same October 2019 document that reveals the one-time buyout fees for Epic’s free games, the company weighed the idea of an “aggressive pursuit model” instead of “winding down” its investment in exclusive games for the store.

The timing is particularly intriguing: Epic was exploring this idea months after it already publicly said it would stop paying for exclusives. We can’t say for sure which strategy Epic actually picked, but “aggressive pursuit” seems likely, when you consider how Epic recently told PC Gamer that “we have more exclusives coming in the next two years than we have published to date.”

Comparing that to the numbers in the document above, it sure sounds like Epic decided to aggressively chase Steam for that bigger piece of the pie. Plus, we now know Epic was considering a “Project Moonshot” to do just that.

Epic’s Project Moonshot would be the Epic Games Store’s biggest push yet.

In November 2019, Epic was planning a “Test Flight” where it would make some of the biggest games on PC free for two whole weeks at a time in a few test markets. It would spend an incredible $46 million to advertise the heck out of the Epic Games Store, in the hopes of driving an estimated 4 million new users to the platform.

And that was just a trial balloon for “Project Moonshot,” an attempt to beat Steam by 2024 by more than tripling Epic’s monthly active users and hitting $1 billion in revenue, primarily by investing even more in “major launches, free games and key sales.”

And while it’s possible the Apple and Google trials might have impacted the company’s plans, the pandemic most certainly didn’t: September 2020 documents show the Test Flight was ridiculously successful, and they make it sound like Project Moonshot is still a go.

While Epic did push back the Test Flight to May and June 2020, the company saw 25 million new non-Fortnite users that May — over six times its original goal. Chart after chart shows a huge increase in engagement, including 350 million hours of non-Fortnite games played during those months, triple what it saw in April and substantially more than in July and August after the test was done. Many of those users seem to have stuck around, with Epic commenting on one slide that there “appears to be a new floor post Test Flight.”

The company’s “2020 Strategy & Tactics Update” lists Project Moonshot’s exact promise of “$1B Revenue & Triple MAU” as Epic’s primary goal, and “Continue Exclusives and Free Games” and “Radically increase awareness of platform” as the ways to make that happen. So don’t be surprised if you start seeing a lot of Epic Game Store ads and a raft of additional exclusives in the months and years to come.