Here's an urgent request.

matthew barbour fortnite

If you popped into a newsagent yesterday - or perhaps even glanced at social media - you might have seen a front page headline about Fortnite, the biggest game in the world.

"Fortnite made me a suicidal drug addict" read the Daily Mirror, its front page telling of a "teen's video game hell".

"Dad saves his son, 17, from death plunge after he gets hooked on online craze" the front page continues.

The exclusive, by a journalist called Matthew Barbour, goes on:

"A boy's obsession with video game Fortnite ruined his life and drove him to a suicide bid.

"His dad had to physically stop him from jumping to his death. Carl Thompson, 17, from Preston, said: 'Fortnite made me a suicidal, thieving, lying drug addict.' "

Pages four and five are a double-page splash in which Carl describes how he climbed to the ledge of his third-floor bedroom window and prepared to leap to his death.

"I was taking speed so I'd stay awake and play all night," Carl is quoted as saying, "but then I started needing more."

Carl reveals he stole from his parents to pay for Fortnite's latest weapons and upgrades.

"I was exhausted doing all-nighters, so my mates said I should try playing with amphetamines. I've always been anti-drugs, but all I wanted to do was play the game more, and this seemed the only way.

"One morning I urinated in a bottle by my desk and drank from another bottle."

The suicide attempt occurred in April. Carl's parents, who say Fortnite is to blame for their son's troubles and expressed their shame at not spotting their son was in a bad place, called in Lancashire-based counsellor Steve Pope "and the lad's life is getting back on track".

At the end of the article we see developer Epic declined to comment, as well as a note to say the names of Carl and his parents were changed at their request. And, interestingly, we see the URL for the website of Steve Pope, what amounts to a plug for the counsellor's business.

The Mirror's story has been roundly criticised on social media, with many in the UK video game industry claiming that by singling out Fortnite, the report over-simplifies suicides and fails to discuss the potential for diagnosed or undiagnosed mental health problems being at play at the time of the teen's suicide attempt.

Video game addiction is a dirty phrase in the industry. I've reported on why I believe we should be more willing to discuss addiction, with games such as Fortnite and FIFA such a huge hit with children. But what's particularly interesting in the case of the Mirror's story is how it came to be in the first place.

Mainstream media often report on case studies such as these - when normal lives go wrong, essentially. Often, these case studies are bought by newspapers and the journalists who work for them from news agencies who in turn have paid people for their stories.

It turns out the author of the Mirror's piece, Matthew Barbour, has form in this regard.

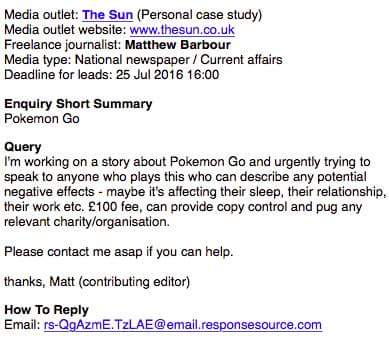

Two years ago, Matthew Barbour searched for a case study online about the negative effects of playing that summer's video game craze: Pokémon Go.

"Maybe it's affecting their sleep, their relationship, their work," Barbour said.

Barbour, who claimed to be a contributing editor of The Sun, offered £100 to anyone who might fit the bill and promised to plug any organisation or charity required.

Eurogamer's then YouTube producer Chris Bratt decided to get in touch in a bid to see how far Barbour was willing to push his agenda. Pretty far, it turned out.

Two years ago when Pokemon Go was the game of the moment, he sent this blanket email via ResponseSource, asking for anyone to describe its "potential negative effects" in exchange for £100. He even suggests a few problems they might like to talk about. (2/8) pic.twitter.com/DL4kTyr2Wn

— Chris Bratt (@chrisbratt) July 31, 2018

So, I emailed him a story to see what the rest of the process was like. I went with the subject header "Pokemon Go is ruining my marriage" and then wrote the most ridiculous tale I could manage. (4/8)

— Chris Bratt (@chrisbratt) July 31, 2018

— Chris Bratt (@chrisbratt) July 31, 2018The next day he calls me for an interview over the phone. This was the bit that blew me away.

He started the phone call by saying that although he figured certain parts of my story had been embellished, that didn't matter, he'd write it anyway. (6/8)

So yeah, those ridiculous headlines you see on the Daily Mirror and the rest? That's how they get there. Fuck that. (8/8)

— Chris Bratt (@chrisbratt) July 31, 2018

Barbour has been caught offering cash for stories before. In 2015, The Pulse, a trade magazine for GPs, reported on Barbour's attempt to pay patients who were negatively affected by the junior doctors' strike for their stories.

"In a request seen by Pulse, Matthew Barbour - who claimed to be contributing editor for the Sun - explains he will offer a 'good fee' for patients with tales of 'a nightmare at A&E' or who 'witness' hospital staff shortages," The Pulse reported.

"We will be looking for patients who have been affected in some way - probably someone who has had an op cancelled or someone who experiences a nightmare at A&E or witnesses staff shortages at a hospital. Anything along these lines would suffice," Barbour wrote.

"We can pay a good fee and also provide complete copy control so you're 100 per cent happy with any write up - so your views are accurately represented."

The Pulse later updated their story to say the Sun issued a statement distancing themselves from Barbour.

On Twitter, the Sun's head of PR Dylan Sharpe said: "The Sun has no position of contributing editor. Matthew Barbour is a freelancer and does not represent the paper nor was he asked for this specific case study request by anyone at The Sun."

In 2013, Barbour was exposed by Private Eye, which published his urgent request for an expert "who will say tattoos will give you cancer". And yes, a fee was offered.

And earlier this year, Barbour took to NetMums to "desperately" request updates from victims of the Manchester bombings. "We can pay a good fee..." Barbour wrote.

For the tattoo and Pokémon Go stories, Barbour used a company called ResponseSource to help find a case study. Here's how it works: journalists post their case study request on Response Source's website. This is then connected to news agencies and public relations people who may be able to provide the relevant case studies.

News agencies are behind many of the headlines you read in the UK press. They often specialise in real life or celebrity stories. Triangle News, for example, was behind a story about a woman who spent over £25,000 on her Disney obsession, and another story about a woman who married a 300 year-old dead pirate. News agencies call on people to sell their stories to them. This can be lucrative for all parties involved. As the story moves up the chain from news agency to national newspaper, thousands of pounds can change hands.

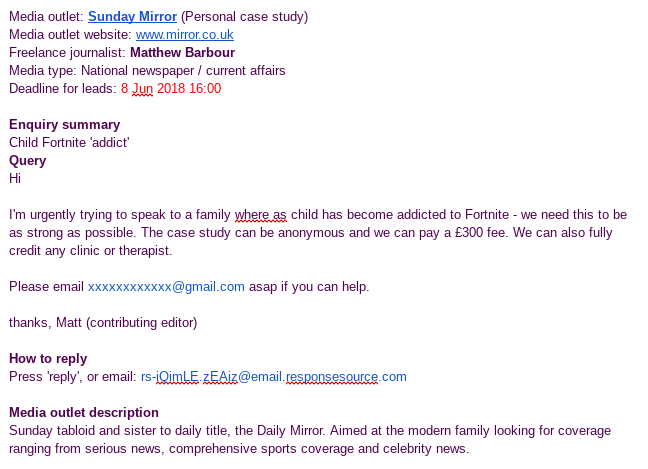

Eurogamer has obtained an email sent by ResponseSource on behalf of Barbour dated 8th June 2018. Barbour, who's working on a story for the Sunday Mirror, wants to "urgently" speak to a family whose child has become addicted to Fortnite. "We need this to be as strong as possible," Barbour wrote. "The case study can be anonymous and we can pay a £300 fee. We can also fully credit any clinic or therapist."

This email, with personal information redacted to protect the identity of our source, is below:

Over email, I asked Barbour a number of questions relating to his Fortnite story in the Mirror:

- Did the teen suffer from any diagnosed or undiagnosed mental health problems at the time of the suicide attempt?

- How did the teen have access to amphetamines? (I can't see this addressed in the story.)

- The story claims Fortnite made the teen "debt-ridden", but I can't see this explained. Who was he in debt with? By how much?

- How did you find the family of the teen who attempted suicide?

- Can you confirm the family of the teen who attempted suicide were paid for their story?

Barbour's response:

"Am I being paid to provide these answers?"

I also asked the Mirror's parent company, Reach, a similar set of questions regarding the backlash to the story. I've yet to hear back, but that's not surprising. This week the company announced it had slumped to a £113m half-year loss after slashing the value of its regional publishing operations. I suspect its PR department is a little busy dealing with that.

And what about Steve Pope, the counsellor who's helping the teen? He's yet to respond to Eurogamer's request for comment (even after multiple phone calls), but it's worth noting Pope is no stranger to the UK media. He's been on ITV's This Morning, in a Jeremy Kyle documentary and on the BBC discussing video game addiction, which he treats at his clinic. That plug in the Mirror won't hurt, will it?

There's no evidence to suggest the Mirror's Fortnite story was fabricated. But when you pull back the curtain and discover how these types of articles are put together, when you understand how some mainstream journalism works, it's hard not to wonder about the motivations of the parties involved.

This kind of story also tarnishes the good work some reporters do in the mainstream media around video games. There is often a divide between those who know games and report on them for "tech" or "games" sections of newspapers, and those who work on the news or features desks of newspapers who are charged with putting a paper together on a tight deadline. This week's Mirror story has shone a light on this divide. Ryan Brown, a freelance journalist who writes about video games for the Mirror's website, took issue with the newspaper's approach.

As a games writer for The Mirror, I'd just like to confirm that this is complete bollocks. I wish they'd conferred with us before printing this. There's no point in having games coverage if we're going to run stuff like this in print.

— Ryan Brown 🎮🇺🇦 (@Toadsanime) July 31, 2018

As I've said, I believe video game addiction is a very real issue the industry should face up to, but the Mirror's reporting is irresponsible to say the least. According to Samaritans, journalists should avoid over-simplification when it comes to stories about suicide.

"Approximately 90 per cent of people who die by suicide have a diagnosed or undiagnosed mental health problem at the time of death," Samaritans points out.

"Over-simplification of the causes or perceived 'triggers' for a suicide can be misleading and is unlikely to reflect accurately the complexity of suicide.

"For example, avoid the suggestion that a single incident, such as loss of a job, relationship breakdown or bereavement, was the cause.

"It is important not to brush over the complex realities of suicide and its devastating impact on those left behind."